NYS Heavy Metals Registry, 2006-2010

- This report, New York State Heavy Metals Registry, 2006 through 2010, is available in Portable Document Format (PDF, 640KB).

The New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) Heavy Metals Registry (HMR) is a tool for the surveillance of adult exposures to arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury. These metals are widely used in industry, and all have the potential to cause illness due to either acute or chronic exposure. While heavy metals have been used by humans for thousands of years and the adverse health effects associated with exposure to them are well known, exposure to these metals continues. Examination of the Registry data can identify exposures in both communities and workplaces, thus allowing for early initiation of measures to help prevent exposures and potential illness.

| Metal | Sample | Reportable At or Above |

|---|---|---|

| Lead | Blood | All levels |

| Cadmium | Blood | 10 nanograms per milliliter |

| Urine | 5 micrograms per liter | |

| Mercury | Blood | 5 nanograms per milliliter |

| Urine | 20 nanograms per milliliter | |

| Arsenic | Urine | 50 micrograms per liter |

The NYSDOH established the HMR in 1980 under Sections 22.6 and 22.7 of the State Sanitary Code (10 NYCRR Part 22, see Appendix A), and reporting to the Registry began in 1982. All clinical laboratories, physicians and health care facilities, both in-state and out of NYS must report the test results of all NYS residents to the NYSDOH. For mercury, cadmium and arsenic, only those tests above specified limits (Table 1) are required to be submitted to NYSDOH. From 1982 to 1986, blood lead levels of 40 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL) or higher were reportable. In 1986, the reportable blood lead level was lowered to 25 µg/dL or higher. Then in 1992, as part of a major childhood lead poisoning initiative, a regulatory change required the reporting of all blood lead results for all age groups, regardless of level (10 NYCRR Part 67, see Appendix A). This reporting has helped track adult blood lead levels over time by verifying trends in both individuals and companies and has allowed NYSDOH to proactively identify adults potentially at risk before their blood lead levels increase further.

Clinical laboratories, physicians and health care facilities report heavy metal test results to the NYSDOH. Once information is received on a person with an elevated level, NYSDOH contacts the person and/or their physician and interviews them to determine the possible sources of exposure, provide advice on appropriate measures to limit future exposures to the individual and his or her family, and answer any questions the individual may have. Additional information about how the HMR operates is provided in Appendix B.

This report presents data for tests conducted from 2006 through 2010, and covers the four metals included in the HMR – arsenic, cadmium, lead and mercury. The number of adults reported since the inception of the Registry is presented for each metal. This report is intended as a resource for programs providing preventive health care and for public health officials concerned with reducing overall morbidity from heavy metals poisonings. Because of the change in the reporting requirement for lead in 1992 and because testing for lead exposure among adults is much more common, lead tests account for approximately 75 percent of the tests added to the HMR each year. Therefore, the majority of this report focuses on the lead reports.

Arsenic

Arsenic is a naturally occurring chemical element. In the environment, it combines with oxygen, chlorine and sulfur to form inorganic arsenic compounds. Inorganic arsenic compounds are used in a number of industrial processes such as in the making of electronics. Fish and shellfish accumulate arsenic, most of which is in a relative non-toxic organic form.1

Exposure to high levels of inorganic arsenic can cause death; exposure to lower levels can result in nausea and vomiting, decreased production of red and white blood cells, abnormal heart rhythm, damage to blood vessels, darkening of the skin and the appearance of small "warts" on the palms, soles and torso. Inorganic arsenic is also a known carcinogen.2

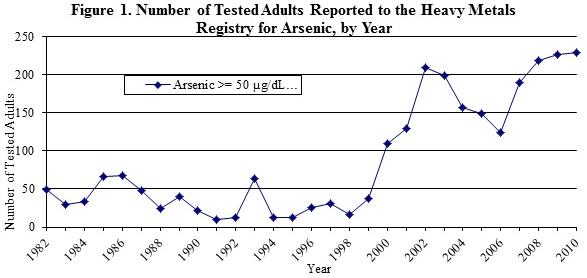

From 1982 through 1999, the number of adults reported to the Registry for arsenic each year was, with a few exceptions, below 50. In 2000, 109 adults were reported. Since then, the number of adults reported continued to vary but remained above 100 and increased to a high of 229 adults in 2010 (Figure 1). This rise is most likely because of an increase in the number of people tested due to greater public awareness that exposure to heavy metals is possible through seafood consumption.

During the years 2006-2010, slightly over 60 percent of the adults reported to the HMR were male, and almost 65 percent were 50 years of age or older (Table 2). For over 80 percent of the adults reported, the source was non-occupational in origin; however, the source could not be identified for another 19 percent. Of the unknown exposures, 89 percent were not interviewed so detailed exposure information could not be obtained. In general, non-occupational sources of arsenic exposure are attributed to eating seafood; over 99.5 percent of the known sources of non-occupational exposure were due to eating seafood, with a few adults that were exposed to arsenic through use of folk medicine and dietary supplements. Because most laboratories do not routinely distinguish between organic and inorganic forms of arsenic when they test, NYSDOH advises people with elevated arsenic results to avoid seafood consumption for two days prior to testing and have another test. This can help to indicate if seafood was the source of the initial arsenic level. In March of 2009, NYSDOH issued advice to healthcare providers asking them to advise their patients to abstain from seafood consumption for at least 48 hours prior to obtaining a urine sample for arsenic testing. As of October 2010, there had not been a reduction in the number of individuals with reportable arsenic levels, indicating that further outreach to healthcare providers may be necessary. There were approximately 1.15 tests reported for each adult, indicating that people with reportable levels are either not being routinely retested, or if they are being retested, their arsenic levels are falling below the reporting level of 50 µg/dL. NYSDOH does not advise routine testing of individuals for arsenic in the absence of identifiable risk factors.

| Number of Adults | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1,011 | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 618 | 61.1 |

| Female | 393 | 38.9 |

| Age | ||

| <29 years | 62 | 6.1 |

| 30-49 years | 296 | 29.3 |

| >50 years | 653 | 64.6 |

| Exposure | ||

| Occupational | 3 | 0.3 |

| Non-occupational | 813 | 80.4 |

| Both | 2 | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 193 | 19.1 |

| Geographic Area | ||

| NYS w/o NYC | 647 | 64.0 |

| NYC | 343 | 33.9 |

| Not in NYS | 21 | 2.1 |

| Total Number of Tests* | 1,163 | |

| * The number of tests adds up to more than the number of adults because adults can have multiple arsenic tests. | ||

Cadmium

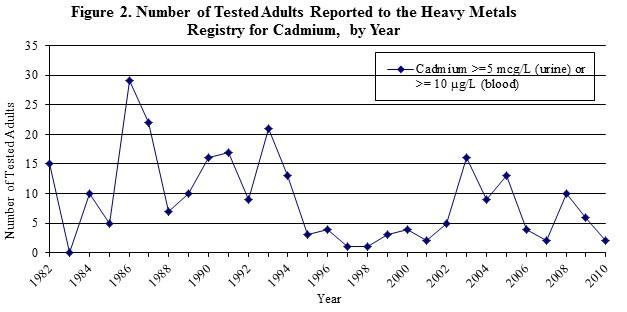

Cadmium occurs naturally in soil and rocks. Because it does not corrode easily, it has many uses including batteries, pigments, metal coatings and plastics.3 Exposure to cadmium can damage the kidneys, lungs and bones.4 Cadmium levels of 10 nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) in blood and 5 µg/L in urine are reportable to NYSDOH. The number of adults with reportable levels for cadmium has varied considerably since the Registry began (Figure 2). However, there have always been fewer than 30 adults reported to the HMR each year. NYSDOH does not advise routine testing for cadmium in the absence of identifiable risk factors.

Between 2006 and 2010, there were 24 adults with elevated cadmium levels reported to the HMR (Table 3). Two-thirds of those reported were male, and almost 80 percent resided outside of New York City (NYC). Seven individuals had known occupational exposures; all of those worked in secondary smelting and refining of nonferrous metals. Three people were exposed to cadmium non-occupationally through their hobbies. All three were artists who worked with cadmium paints, pigments and/or inks in their art work. The exposure source could not be identified for fourteen individuals, however of the unknown exposures, 50 percent were not interviewed so detailed exposure information could not be obtained.

| Number of Adults | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 24 | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 15 | 62.5 |

| Female | 9 | 37.5 |

| Age | ||

| <29 years | 1 | 4.2 |

| 30-49 years | 10 | 41.7 |

| >50 years | 13 | 54.2 |

| Exposure | ||

| Occupational | 7 | 29.2 |

| Non-occupational | 3 | 12.5 |

| Both | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 14 | 58.3 |

| Geographic Area | ||

| NYS w/o NYC | 19 | 79.2 |

| NYC | 5 | 20.8 |

| Total Number of Tests* | 45 | |

| * The number of tests adds up to more than the number of adults because adults can have multiple cadmium tests. | ||

Lead

Lead, a naturally occurring element, is found in all parts of our environment. Lead from deteriorating lead-based paints, ceramic products, caulking, leaded gasoline and pipe solder are primarily responsible for exposures in children. Workers can be exposed to lead by creating dust or fumes during every day work activities with products that include lead, such as paint, ammunition, solder, and leaded cables. Other non-occupational exposures can include contaminated spices and dietary supplements. Exposure to lead can affect the brain and other parts of the nervous system, reproductive system, kidneys, digestive system, and the body's ability to make blood.5

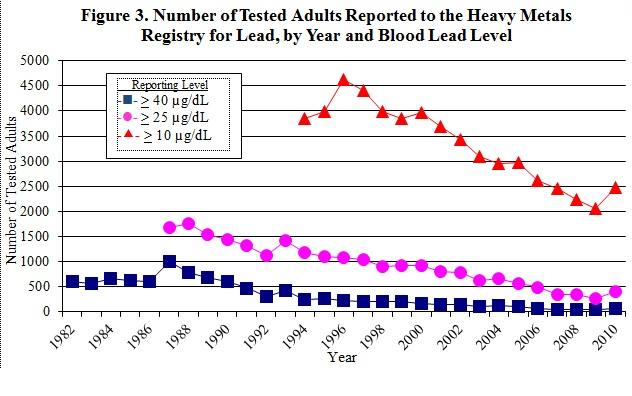

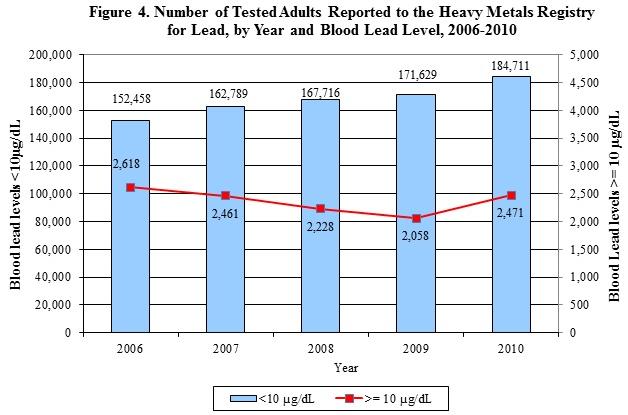

The results of all blood lead tests, regardless of level, performed on individuals residing or employed in NYS are reported to the HMR. Adults with blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL are reported to the NYSDOH, but because of the magnitude of these reports (150,000-200,000 are received annually), they are not case matched. Therefore, only information reported by the laboratory (name, address, date of birth, ethnicity, and blood lead level) is available on adults with blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL.6 Only adult (16 years and older) blood lead tests with results at or above 10 µg/dL are added to the HMR. Between 2006 and 2010, 7,918 individuals residing or employed in NYS were reported to the HMR. There has been a steady decrease in the number of elevated blood lead levels reported to the HMR since the mid-1990's (Figure 3), until 2010 when a slight increase was observed. Meanwhile, there has been an increase in the number of individuals with blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL (Figure 4). Assuming one test per individual for those tests that are less than 10 µg/dL indicates that approximately 98 percent of all adults tested in 2006 had blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL. In 2010, this increased to over 99 percent of all adults tested. Females represented over 76 percent of those adults with blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL (data not shown). Although NYS does not require testing all pregnant women for blood lead, NYSDOH regulations state that a health care provider should test pregnant women at high risk, and the state has established guidelines for health care practitioners to assist in determining a woman's risk of lead poisoning on her initial prenatal visit.8 The high number of females with low blood lead levels could be a result of an increase in women receiving pre-natal blood lead tests.

There were three distinct phases for the reporting of blood lead test results to the HMR, associated with changes in reporting requirements. From the start of the HMR in 1982 to 1986, only test results greater than or equal to 40 µg/dL ( , Figure 3) were required to be reported. From 1987 to 1993, test results of 25 µg/dL and greater (

, Figure 3) were required to be reported. From 1987 to 1993, test results of 25 µg/dL and greater ( , Figure 3) were reportable. In 1992, a NYSDOH regulation required the reporting of all blood lead results for all ages, regardless of level. This requirement became effective in 1994 (10 NYCRR Part 67, see Appendix A). Since that time (1994) all adult blood lead levels greater than or equal to 10 µg/dL have been reported to the HMR (

, Figure 3) were reportable. In 1992, a NYSDOH regulation required the reporting of all blood lead results for all ages, regardless of level. This requirement became effective in 1994 (10 NYCRR Part 67, see Appendix A). Since that time (1994) all adult blood lead levels greater than or equal to 10 µg/dL have been reported to the HMR ( , Figure 3). As mentioned previously, because of the large number of reports of blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL, they are not case matched and are not included in the HMR. Another factor that may have contributed to the increase in reporting to the HMR shown in Figure 3 is an increase in testing following enactment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Lead in Construction Standard in 1993 (29 CFR 1926.62).9 This standard requires blood lead testing for construction workers with lead exposure. While these changes increased the number of reports of blood lead levels to the HMR, the number of adults with blood lead levels of 10 µg/dL or greater has steadily decreased since 1996, following the national trends of decreasing blood lead levels in adults and children (Figure 3).

, Figure 3). As mentioned previously, because of the large number of reports of blood lead levels less than 10 µg/dL, they are not case matched and are not included in the HMR. Another factor that may have contributed to the increase in reporting to the HMR shown in Figure 3 is an increase in testing following enactment of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Lead in Construction Standard in 1993 (29 CFR 1926.62).9 This standard requires blood lead testing for construction workers with lead exposure. While these changes increased the number of reports of blood lead levels to the HMR, the number of adults with blood lead levels of 10 µg/dL or greater has steadily decreased since 1996, following the national trends of decreasing blood lead levels in adults and children (Figure 3).

In general, tested adults with blood lead levels 10 µg/dL and greater reported to the HMR were primarily males 39 to 49 years of age, and more than half resided in NYS outside of NYC (Table 4). Although approximately 80 percent of those reported are male, gender distribution varies by blood lead level (Table 5). Twenty-two percent of those with blood lead levels between 10 and 25 µg/dL and 27 percent of those with the highest blood lead levels (60 µg/dL and greater) are female. The highest blood lead levels among females were all associated with non-occupational exposures (data not shown). For both genders, as the blood lead levels increase, a higher percent of the exposures were associated with non-occupational sources such as residential remodeling, use of folk medicine/dietary supplements and pica. Almost 60 percent of the tested adults with unknown exposures were not interviewed, so detailed exposure information could not be obtained.

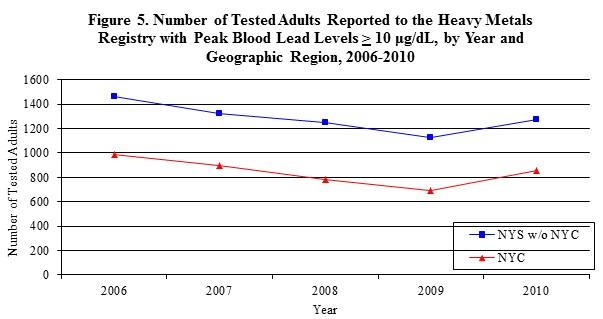

Changes in the number of people reported to the HMR from 2006 through 2010 are similar for NYC and the rest of the state (Figure 5). The change in blood lead levels from 2006 through 2010 is similar for those in NYC and those in the rest of the state (Figure 5).

| Number of Adults | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 7,918 | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6,315 | 79.8 |

| Female | 1,603 | 20.2 |

| Age | ||

| <29 years | 2,014 | 25.4 |

| 30-49 years | 4,001 | 50.5 |

| >50 years | 1,899 | 24.0 |

| Unknown | 4 | 0.1 |

| Exposure | ||

| Occupational | 2,955 | 37.3 |

| Non-Occupational | 894 | 11.3 |

| Both | 100 | 1.3 |

| Unknown | 3,969 | 50.1 |

| Geographic Area | ||

| NYS w/o NYC | 4,126 | 52.1 |

| NYC | 2,988 | 37.7 |

| Out of state | 712 | 9.0 |

| Unknown | 92 | 1.2 |

| Total Number of Tests* | 35,207 | |

| * The number of tests adds up to more than the number of adults because adults can have multiple lead tests. | ||

| Tested Adults | Peak Blood Lead Levels (µg/dL) | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-24 | 25-39 | 40-59 | 60+ | |||||||||

| N | %* | N | %* | N | %* | N | %* | N | %* | |||

| 6,496 | 1,155 | 234 | 33 | 7,918 | ||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 5,076 | 78.1 | 1,018 | 88.1 | 197 | 84.2 | 24 | 72.7 | 6,315 | 79.8 | ||

| Female | 1,420 | 21.9 | 137 | 11.9 | 37 | 15.8 | 9 | 27.3 | 1,603 | 20.2 | ||

| Age | ||||||||||||

| <29 years | 1,692 | 26.1 | 264 | 22.9 | 48 | 20.5 | 10 | 30.3 | 2,014 | 25.4 | ||

| 30-49 years | 3,240 | 49.9 | 633 | 54.8 | 111 | 47.4 | 17 | 51.5 | 4,001 | 50.5 | ||

| >50 years | 1,560 | 24.0 | 258 | 22.3 | 75 | 32.1 | 6 | 18.2 | 1,899 | 24.0 | ||

| Unknown | 4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.1 | ||

| Exposure | ||||||||||||

| Occupational | 1,997 | 30.7 | 804 | 69.6 | 140 | 59.8 | 14 | 42.4 | 2,955 | 37.3 | ||

| Non-Occupational | 557 | 8.6 | 249 | 21.6 | 71 | 30.3 | 17 | 51.5 | 894 | 11.3 | ||

| Both | 51 | 0.8 | 37 | 3.2 | 10 | 4.3 | 2 | 6.1 | 100 | 1.3 | ||

| Unknown | 3,891 | 59.9 | 65 | 5.6 | 13 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 3,969 | 50.1 | ||

| Geographic Area | ||||||||||||

| NYS w/o NYC | 3,379 | 52.0 | 605 | 52.4 | 124 | 53.0 | 18 | 54.6 | 4,126 | 52.1 | ||

| NYC | 2,477 | 38.1 | 404 | 35.0 | 93 | 39.7 | 14 | 42.4 | 2,988 | 37.7 | ||

| Out of NY | 559 | 8.6 | 137 | 11.9 | 15 | 6.4 | 1 | 3.0 | 712 | 9.0 | ||

| Unknown | 81 | 1.3 | 9 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | 92 | 1.2 | ||

| * Note: Due to rounding, some percentage columns may not sum to 100. | ||||||||||||

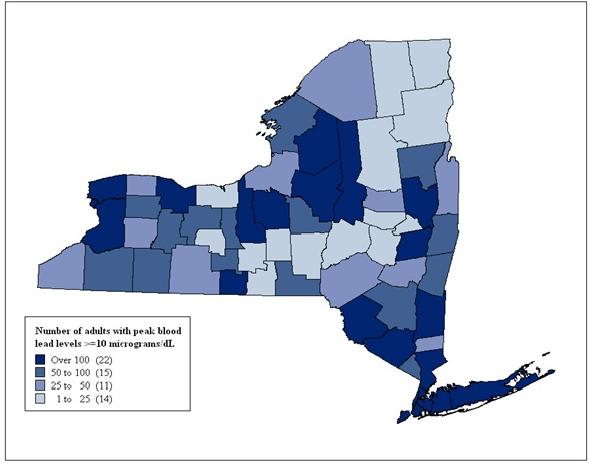

The county of residence for individuals reported with blood lead levels greater than or equal to 10 ug/dL is displayed in Figure 6. While this figure shows where people who get tested and also are exposed to lead through their occupations or other activities live, there is no obvious pattern in the geographic distribution of the people tested. There are a number of individuals who are exposed to lead due to work in NYS, but reside elsewhere (Table 5).

Figure 6. Distribution of Tested Adults Reported with Peak Blood Lead Levels ≥10 ug/dL, by County of Residence, 2006-2010

As used in this report, the term occupational includes exposures that are classified as occupational exposures only, or both occupational and non-occupational. The primary sources of lead for occupationally exposed individuals with elevated blood lead levels (greater than or equal to 10 µg/dL) are displayed in Table 6. Individuals included in the "other" category had occupational exposures that were not included in any of the categories described in Table 6. These people were primarily machine operators, assemblers and non-construction laborers working in the manufacture of primary metals, and electronics and electrical equipment workers.

| Exposure Source | Blood Lead Levels (µg/dL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-24 | 25-39 | 40-59 | >60 | Total | |

| Bridge Work | 485 | 369 | 64 | 5 | 923 |

| Cables/Wires Work | 51 | 32 | 5 | 0 | 88 |

| Foundry/Smelting | 40 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 61 |

| Iron/Steel Structures | 111 | 47 | 13 | 1 | 172 |

| Lead Abatement | 68 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 97 |

| Lead Glass/Powder | 29 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 54 |

| Metal Recycling | 26 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 43 |

| Radiator Repair | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Residential Remodeling | 58 | 41 | 23 | 2 | 124 |

| Stained Glass | 23 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 41 |

| Target Shooting | 48 | 23 | 7 | 2 | 80 |

| Other | 1,086 | 226 | 25 | 5 | 1,342 |

| Unknown | 14 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 2,046 | 841 | 152 | 16 | 3,055 |

The primary sources of non-occupational exposure among individuals with blood lead levels greater than or equal to 10 µg/dL are displayed in Table 7. Individuals with non-occupational exposures are primarily exposed through the use of folk medicines/dietary supplements, during target shooting and during residential remodeling. Lead has been found in some traditional folk medicines used by South Asian, Middle Eastern and Hispanic cultures. In some cultures, people believe that lead can be useful in treating ailments such as arthritis, infertility, and upset stomach.10 These exposures primarily occur in the NYC area, and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has developed many outreach materials to address these exposures.11 Exposure to lead is also a concern during the renovation/remodeling of any home built before 1978, after which lead was banned from household paint. NYSDOH has developed outreach materials and staff routinely assists homeowners in assessing and reducing their potential for exposure. People can also be exposed to lead from target shooting since most ammunition contains lead in either the bullet or the primer. Details about an industrial hygiene evaluation of two shooting ranges, are presented elsewhere in this report. The highest non-occupational blood lead levels (over 60 µg/dL) occur among those using folk medicines/dietary supplements and those with retained bullet fragments. Retained bullet fragments in a person can leach lead over time, especially if a bullet is located near or in a skeletal joint.12

| Exposure Source | Blood Lead Levels (µg/dL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-24 | 25-39 | 40-59 | >60 | Total | |

| Incidental Ingestion, Pica | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Cookware | 13 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 17 |

| Household Environment/Home Product2 | 48 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 57 |

| Casting of Bullets, Fishing Sinkers | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| Folk Remedies | 232 | 68 | 22 | 4 | 326 |

| Hobby, Jewelry, Crafts | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Retained Bullet Fragments3 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 36 |

| Residential Remodeling | 63 | 43 | 7 | 1 | 114 |

| Target Shooting | 84 | 83 | 27 | 0 | 194 |

| Unknown | 66 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 82 |

| Total | 557 | 249 | 71 | 17 | 894 |

|

|||||

Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance

NYS participates in the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) surveillance program, Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology and Surveillance (ABLES), which is a state-based surveillance program of laboratory-reported adult blood lead levels. For the ABLES program, adults are defined as persons 16 years or older. The objective of the ABLES program is to build state capacity to improve adult blood lead surveillance programs and to measure trends in adult blood lead levels. NYSDOH submits lead data from the HMR to the ABLES program twice a year. Nationally, 41 states participate in ABLES. OSHA has used national program data to identify industries where elevated blood lead levels indicate a need for national focus. Over the past 17 years, a 50 percent decrease in the national prevalence rates of blood lead levels 25 µg/dL or greater has been documented using ABLES data. NYSDOH has used ABLES data to identify trends and identify areas for targeted interventions. NIOSH has notified NYSDOH that due to federal budget cuts, funding for the ABLES programs in all states ceased effective August 31, 2013.

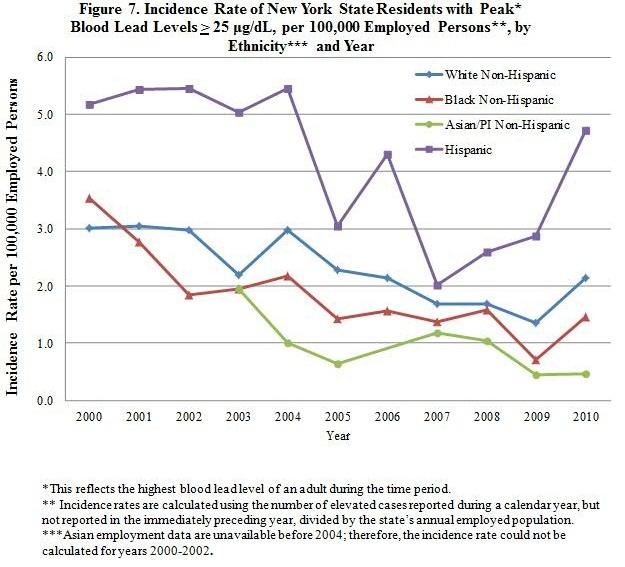

Disparities in Lead Exposure

As shown in Figure 7, there has generally been a steady decline in the incidence rate of elevated adult blood lead levels (25 µg/dL or greater) among various groups of New Yorkers during the time period 2000-2010. However, Hispanics still have almost double the rate of elevated blood lead levels compared to other groups.

Hispanic females made up almost 40 percent of all females reported to the HMR with blood lead levels 25 µg/dL or greater between 2000 and 2010 with a known ethnicity. More than 75 percent of these Hispanic women had non-occupational exposure due to folk remedy use, and approximately 80 percent resided in NYC. Most of the Hispanic men reported to the HMR, 70 percent of whom reside in the NYC area, were exposed to lead through their jobs as house painters. The data show the continuing need for educational outreach to Hispanic women and men.

Mercury

Mercury occurs naturally in the environment in several forms. One common form is metallic mercury (also called elemental mercury). Metallic mercury is a silvery, odorless liquid that can evaporate at room temperature, becoming a vapor. Mercury can also combine with other chemicals to form inorganic or organic mercury compounds. Inorganic mercury is mercury combined with other chemical elements such as chlorine, sulfur or oxygen. Organic mercury is mercury combined with carbon-based compounds. One common form of organic mercury is methylmercury, which is produced by microorganisms in water and soil, and accumulates in fish. Exposure to high levels of mercury can damage the nervous system and cause irritability, shyness, tremors, changes in vision or hearing and memory problems. Mercury can also harm the kidneys and developing fetus.13 People are exposed to metallic mercury when they inhale the vapors. People can be exposed to inorganic and organic mercury when they eat foods or other products contaminated with mercury.

Urine and blood testing are the accepted methods to assess mercury exposure for medical purposes. The type of test performed depends upon the form of mercury to which a person may have been exposed. An elevated urine test for mercury indicates an elemental or inorganic source of mercury exposure. An elevated blood test for mercury indicates a recent exposure to a high concentration of mercury vapor or exposure to an organic mercury source (for example, methylmercury from a recent fish meal). Levels of mercury that are reportable to the NYSDOH are 5 ng/mL in blood and 20 ng/mL in urine.

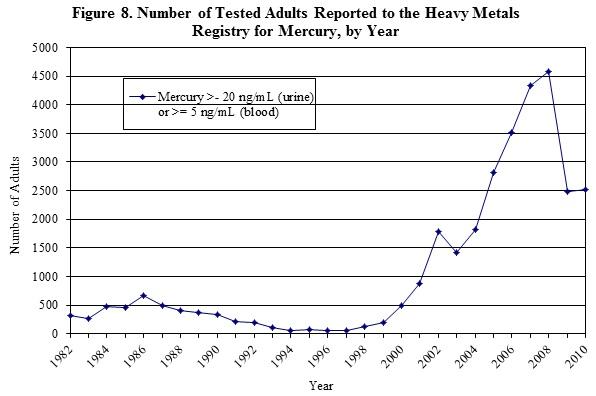

The number of adults reported to the HMR began to sharply increase in 2000, peaking at 4,579 adults reported in 2008 (Figure 8). The number of reported adults previously peaked at over 600 in 1986. The number then declined until 1994, remaining steady at less than 100 adults until 1998 when the number of adults with reportable mercury tests began to increase. NYSDOH analyses of interview records found that approximately 99 percent of adults reported to the HMR with identifiable exposures during 2001-2008 had non-occupational exposures resulting from seafood consumption. Common types of fish consumed include salmon, tuna and swordfish, with 90 percent of adults eating seafood multiple times per week. There was a statistically significantly higher mean blood mercury level among those who ate fish daily compared to those who ate fish less frequently. Data from this study were presented at the 2008 Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) meeting and published in the Journal of Community Health in June 2013.14 This information was also shared with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to assist with their outreach efforts.

Between 2006 and 2010, 17,421 adults were tested for mercury. Because some people were tested more than once, there were a total of 20,628 tests during this time period (Table 8). These were almost equally divided between males (49.5%) and females (50.5%), and slightly more than half were 50 years of age and older. Almost 60 percent of those tested were residents of NYC.

| Number of Adults | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 17,421 | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 8,630 | 49.5 |

| Female | 8,791 | 50.5 |

| Age | ||

| <29 years | 1,463 | 8.4 |

| 30-49 years | 6,706 | 38.5 |

| >50 years | 9,252 | 53.1 |

| Exposure | ||

| Occupational | 24 | 0.1 |

| Non-Occupational | 3,597 | 20.7 |

| Both | 8 | 0.1 |

| Unknown | 13,792 | 79.1 |

| Geographic Area | ||

| NYS w/o NYC | 6,640 | 38.1 |

| NYC | 10,244 | 58.9 |

| Out of State/Unknown | 537 | 3.1 |

| Total Number of Tests* | 20,628 | |

| * The number of tests adds up to more than the number of adults because many adults have multiple mercury tests. | ||

Research and Intervention Activities

NYSDOH continually reviews and evaluates data from this Registry and uses this information to design and implement prevention efforts. For example, data from the HMR have proven to be an important tool in research to identify situations in which adult lead exposure is occurring and the consequences of the exposures. Some examples of these research and intervention activities are listed below.

Identifying Causes of Elevated Blood Lead Levels

- An analysis of the HMR lead data showed that although there has been an overall increase in the number of tests conducted, the majority of the increase is among those with the lowest blood lead levels. There has been a decline in the number of adults with blood lead levels 25 µg/dL or greater. The analysis also found that many of the markedly elevated blood lead levels (≥60 µg/dL) are due to non-occupational exposures, including exposure from target shooting and residential remodeling. These findings were published in Public Health Reports.15

- Another research study found that 14 percent of children with elevated blood lead levels in NYS lived in homes in which renovation, repair and painting activities had occurred.16 Resident owners or tenants performed 66 percent of the renovation, repair and painting work themselves, exposing themselves and their children to lead through these activities.

- Further analyses on lead exposure among target shooters, published in the Archives of Environmental and Occupational Health17, found that hobby target shooters are at significant risk of having elevated blood lead levels. Target shooters were reported more frequently with blood lead levels ≥40 µg/dL than individuals with occupational exposures to lead.

Actions to Help Reduce Blood Lead Levels

- To help reduce exposure to lead from residential remodeling activities, NYSDOH provided lead exposure training programs to 1,257 municipal code enforcement officers statewide regarding lead exposure. Results of a post-training survey showed that over 75 percent of the survey respondents indicated that the training improved their knowledge of lead and ability to identify hazards; 60 percent of the respondents indicated that the training course changed the way they addressed lead during a housing inspection. NYSDOH also provided similar training for hardware store employees, and further disseminated the information through articles published in The Journal of Light Construction18 and Rental Housing.19

- NYSDOH identified a need for information about worker protection from lead exposure to a Portuguese speaking population. Therefore, the NYSDOH brochure "Lead on the Job: A Guide for Workers" was translated into Portuguese. This brochure is also available in Spanish, Greek and Polish.

- NYSDOH launched the Aim at Lead Safety outreach campaign to provide education in the form of fact sheets, posters and brochures to shooting ranges throughout NYS about methods to limit exposure to lead (see http://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/lead/target_shooting/).

Investigating Women with Low Blood Lead Levels

- Research that was focused on women with low blood lead levels, examined why they were tested, whether there were identifiable sources of exposure and, for women who were pregnant, possible associations with decreased fetal growth.20,21 Women with low blood lead levels were tested primarily because they were pregnant, although few had a potential source of lead exposure. Low blood lead levels were associated with a small risk of decreased birth weight but were not related to preterm birth or having babies that were small for gestational age.

Special Highlight: Lead Exposure in Recreational and Occupational Shooters

Background

Lead is commonly used in the manufacture of bullets. People who shoot at firing ranges, either because of their employment or for recreation, have been reported to the HMR since its inception. The number of shooters annually reported to the HMR has increased modestly during the past 10 years. This increase may be due to: a) an increase in the number of shooters, b) an increase in shooters who receive blood lead tests, c) an increase in exposure levels, or d) a combination of these and/or other factors. Anecdotal information suggests that most shooters do not have blood lead tests. Most indoor shooting ranges have ventilation systems which, if properly operating, can help to reduce the amount of airborne lead to which shooters are exposed. Many shooters and range owners believe that the ventilation systems protect them from lead exposure and that additional precautions are unnecessary. However, blood lead testing is recommended for all shooters who use leaded bullets, especially if they use an indoor range.

Findings of Industrial Hygiene Evaluations and Interviews

During 2009, NYSDOH performed industrial hygiene evaluations at two law enforcement indoor shooting ranges to compare personal lead exposures to shooters using leaded and non-lead primer ammunition during normal training activities. In most ammunition, the primer contains an initial explosive, which ignites the powder in the bullet casing to propel the bullet from the gun. The explosive material in the primer may contain lead compounds or non-lead compounds. In these evaluations, NYSDOH collected air and surface dust samples for lead during each visit. For shooters using non-lead primer ammunition, the mean personal breathing zone exposure level was 3.5-times higher than the OSHA Permissible Exposure Limit (PEL) (50 micrograms of lead per cubic meter of air (µg/m3) of air) and nearly 4-times higher than the exposure level for shooters using leaded primer ammunition. The higher personal breathing zone exposures for shooters using non-lead ammunition were associated with poor housekeeping practices and substantially higher surface lead contamination in that shooting range. Findings of this evaluation highlighted the relative contribution of surface lead contamination to airborne exposure during routine activities in indoor shooting ranges. Using non-lead primer ammunition did not provide the expected benefits in this range due to the ineffective housekeeping programs. The findings and recommendations from this study were highlighted in a report by the National Research Council22 as well as published in the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene in March 2012.23

Workers, shooters and family members have also been identified through HMR interviews as being lead poisoned by "take-home" lead. Lead dust can settle on clothes, skin and hair and be picked up on shoes in the range. This "take-home" lead dust has been found to be carried to cars and homes where it can then harm family members as well. Other activities that have been found to contribute to lead poisoning include casting bullets, reloading ammunition or cleaning (tumbling) shell casings at home or on their properties.

Recommendations

These evaluations suggest that a broad spectrum of efforts is needed to better protect range instructors, workers who clean shooting ranges, and shooters. Some recommendations that DOH has developed include:

- Range management should provide an effective housekeeping program that includes frequent cleaning of walls, floors, ceilings, traps, and ventilation. Wet cleaning or other effective dust suppression methods should be used to clean the range and ancillary areas and surfaces. Ranges should never be dry swept. One police range abandoned its practice of dry sweeping the floor after the industrial hygiene visit and evaluation.

- Range management should increase the availability and use of ammunition with a lower potential for toxicity (e.g., lead-free primers, jacketed bullets). Shooters should also be encouraged to use this type of ammunition.

- Range management should implement a blood lead testing program, including blood lead level monitoring by a physician on a regular basis, to help prevent short-and-long term health effects. Range instructors, cleaning staff and people who shoot on a regular basis should participate in the program.

- Range management should provide personal protective equipment to range instructors and cleaning workers. This equipment may include NIOSH approved respirators as well as work clothing, shoes and head coverings. Employees should be advised to shower and change clothes/shoes before leaving the range. Work clothing should be disposable or laundered separately to prevent contamination and "take-home" lead. This recommendation applies to shooters as well. They should keep range clothing, footwear, and hats separate from street clothing and wash range clothing separate from family clothing and household items.

These findings, as well as other studies, demonstrate that lead protection in shooting requires a combination of steps including lead hazard awareness, meticulous housekeeping within the range, and good personal hygiene. The efforts of NYSDOH have helped to make range management and shooters aware of the lead hazards when shooting, identified range staff and shooters with elevated blood lead levels, and provided range management and shooters with effective guidance to reduce lead exposure.

References

- 1 New York State Department of Health Heavy Metals Surveillance. Arsenic. Available at: http://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/workplace/heavy_metals_registry/arsenic.htm. Accessed May 2011.

- 2 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2007. Toxicological Profile for Arsenic (Update). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- 3 New York State Department of Health Heavy Metals Surveillance. Cadmium. Available at:http://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/workplace/heavy_metals_registry/cadmium.htm. Accessed May 2011.

- 4 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2008. Toxicological Profile for Cadmium (Draft for Public Comment). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- 5 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 2007. Toxicological Profile for Lead (Update). Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- 6 Zhu M. Maternal Exposure to Lead and Fetal Growth and Hypertension in Pregnancy. Ph.D. Dissertation, State University of New York, Albany, 2009.

- 8 New York State Department of Health, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, District II. Lead poisoning prevention guidelines for prenatal care providers. Albany (NY): New York State Department of Health; June 2009. Available at: http://www.health.ny.gov/publications/2535.pdf. Accessed May 2011.

- 9 United States Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Regulations for Construction (Standards – 29 CFR 1926.62). https://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10641. Updated March 2012. Accessed September 2013.

- 10 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Environmental Health. Folk Medicine. http://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/tips/folkmedicine.htm . Updated June 2009. Accessed November 2012.

- 11 New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Remedies or Herbal Medicines Containing Lead. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/lead/lead-herbalmed-in.shtml#q1 Accessed October 2012.

- 12 Rehman MA, Umer M, Sepah YJ, Wajid MA. Bullet-induced synovitis as a cause of secondary osteoarthritis of the hip joint: A case report and review of literature. Journal of Medical Case Report, 2007,1:171.

- 13 Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1999. Toxicological Profile for Mercury. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service.

- 14 Fletcher AM, Gelberg KH. An Analysis of Mercury Exposures Among the Adult Population in New York State. Journal of Community Health, 2013:38(3): 529-537.

- 15 Gelberg KH, Fletcher AM. Adult blood lead reporting in New York State - 1994 to 2006. Public Health Rep, 2010; 125(1).

- 16 Franko EM, Palome JM, Brown MJ, Kennedy CM. Children with elevated blood lead levels related to home renovation, repair, and painting activities - New York State, 2006-2007. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep, 2009; 58(3): 55-58.

- 17 Gelberg KH, DePersis R. Lead exposure among target shooters. Arch Environ Occup Health, 2009; 64(2): 115-119.

- 18 Franko EM. New rules for lead-safe remodeling. The Journal of Light Construction, 2009; 27(8):61-64.

- 19 Franko E. New rules to remodel right. Rental Housing of Northern Alameda County, 2009; VI(7):8,10,35.

- 20 Zhu M, Fitzgerald EF, Gelberg KH, Lin S, Druschel C. Maternal low-level lead exposure and fetal growth. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2010; Vol 118(10):1471-1475.

- 21 Zhu M, Fitzgerald EF, Gelberg KH. Exposure sources and reasons for testing among women with low blood lead levels. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. Published online 03 May 2011: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09603123.2010.550035

- 22 National Research Council. Potential Health Risks to DOD Firing-Range Personnel from Recurrent Lead Exposure. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2012.

- 23 Scott E, Pavelchak N, DePersis R. Impact of Housekeeping on Lead Exposure in Indoor Law Enforcement Shooting Ranges. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene, 2012, 9:3, D45-D51.

Appendix A: State Regulations for Reporting Heavy Metals

22.6 Reporting heavy metals in blood and urine. Every physician, clinical laboratory and health facility in attendance of a person with a blood or urine test resulting in a value at or above those listed in section 22.7 of this Part, shall report such occurrence to the State Commissioner of Health within 10 days of the receipt of the results of such test. The report shall be on such forms as prescribed by the State Commissioner of Health.

Historical Note: Sec filed May 14, 1981 eff. Dec. 1, 1981.

22.7 Reportable levels of heavy metals in blood and urine. For purposes of section 22.6 of this Part, the following levels of heavy metals in blood and urine samples are reportable to the State Commissioner of Health:

| Metal | Sample | Reportable At or Above |

|---|---|---|

| Lead | Blood | All levels |

| Cadmium | Blood | 10 nanograms per milliliter |

| Urine | 5 micrograms per liter | |

| Mercury | Blood | 5 nanograms per milliliter |

| Urine | 20 nanograms per milliliter | |

| Arsenic | Urine | 50 micrograms per liter |

Historical Note: Sec filed May 14, 1981, and filed Sept. 11, 1986, eff. Sept. 11, 1986

Subpart 67-3

REPORTING OF BLOOD LEAD LEVELS

SEC 67-3.1 Laboratory reporting of blood lead levels for public health follow up

Section 67-3.1 Laboratory reporting of blood lead levels for public health follow up.

(a) For purposes of this Subpart, laboratory shall mean any laboratory that holds a permit issued in accordance with Public Health Law Article 5, Title V and is authorized to conduct blood lead analyses.

(b) Laboratories shall report the results of all blood lead analyses performed on residents of New York State to the Commissioner of Health and to the local health officers in whose jurisdictions the subjects of the tests reside. If the laboratory reports electronically to the Commissioner of Health in accordance with subdivision (e) below, the Department of Health shall notify the appropriate local health officer of the test results and the laboratory shall be deemed to have satisfied the reporting requirements of this section.

Appendix B: Overview of Heavy Metals Registry Program Operations

Clinical laboratories, physicians and health care facilities can report heavy metal test results electronically through the internet or manually on paper forms to the DOH. All information reported to the Registry is confidential, and records and computer files are maintained in accordance with DOH regulations concerning medical data containing individual identifiers. Access to the data by anyone other than Registry personnel is restricted and carefully monitored so that confidentiality is maintained. Approximately 99% of all tests for lead were submitted electronically. This was similar for tests of other heavy metals: 95% of arsenic, 75% of mercury, and 100% of cadmium tests were all submitted electronically.

Once information is received on a person with an elevated level, DOH contacts the person and/or their physician and interviews them to determine the possible sources of exposure, provide advice on appropriate control measures to limit future exposures to the individual and his or her family, and answer any questions the individual may have. DOH also collects demographic information, such as level of education, primary language spoken, and ethnicity along with information about the subject's work and home environments. When the exposure is work-related, DOH gathers information on the employer, work location, protection measures in place and whether coworkers are also potentially exposed. Both Spanish- and French-speaking interviewers are available, and there is access to individuals fluent in several additional languages and dialects including Polish, Russian, Chinese, and Portuguese. Following the interview, DOH provides individuals with brochures appropriate to their exposure sources describing methods to reduce exposure, along with the telephone number of the local state-sponsored occupational health clinic for in the event they wish to pursue additional follow-up on their test results (see Appendix B for a list of the occupational health clinics).

DOH performs the contacts described above for all individuals with reportable levels of arsenic and cadmium, or reportable urine mercury level. For mercury in blood, many years of experience have shown us that lower levels of blood mercury are almost always due to eating freshwater fish and seafood.[23] Therefore, only those individuals with blood mercury levels at or above 25 ng/mL are interviewed. Currently, interviews are conducted for lead exposures of women of childbearing age (ages 16-45), and 16 and 17 year olds with blood lead levels greater than or equal to 10 µg/dL. For all other adult, the interviews are conducted for anyone with blood lead levels at or above 15 µg/dL. From 2007 through February 2009, women of childbearing age were interviewed at blood lead levels greater than or equal to 15 µg/dL, while all other adults reported to the HMR were interviewed at levels greater than or equal to 25 µg/dL. Prior to 2007, all adults were interviewed at blood lead levels greater than or equal to 25 µg/dL. Consequently, for the earlier years (prior to 2007), there is incomplete demographic information for some of the lower blood levels. All other children are followed by the Childhood Lead Poisoning Primary Prevention Program.

When DOH identifies a workplace with employees with high or persistently elevated heavy metal levels, DOH conducts follow-up with the employer. For situations where an employer has not previously had an employee who was reported to the HMR, an industrial hygienist contacts the company to determine the exposure circumstances, learn whether coworkers are at risk and assess whether the company is taking appropriate measures to control exposures. With all contacts, the industrial hygienist protects the confidentiality of the individual reported. An important focus of these efforts is smaller businesses that do not have either full-time medical or industrial hygiene resources to evaluate their worksites. At a minimum, DOH provides advice over the telephone, with a follow-up letter summarizing the recommendations. Depending on the severity or persistence of the problem, or the uniqueness of the source of exposure, DOH may ask for permission to conduct an on-site industrial hygiene evaluation. That evaluation is then followed by a written report that is submitted to the employer and to the union representative, if applicable. Between 2006 and 2010, there were 522 employers identified with at least one employee reported to the HMR with occupational exposures to lead, 14 employers identified for occupational exposures to mercury, 3 for occupational exposures to arsenic and 2 for occupational exposures to cadmium.

In all cases, DOH's goal is to reduce exposure to all heavy metals. For workplace exposures, DOH recommendations are guided by the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards and the experience of the industrial hygienists in addressing similar exposures. In these instances, DOH encourages employers to implement site-specific exposure reduction measures and monitoring to help assure that exposures have been reduced.

DOH recently conducted a full program evaluation for the HMR and is in the process of implementing changes to the Registry. The first of these changes involved lowering the blood lead level of those interviewed. Based on recent research about the toxicity of lead at low dose, NYSDOH dropped the interview levels in March 2009 from 25 µg/dL to 10 µg/dL and above for all women and all 16 and 17 year olds; and interviews all others with blood lead levels of 15 µg/dL and above. Since NYS is currently the only state to be conducting adult interviews and follow-up at these low levels, an evaluation was conducted and presented at the annual Adult Blood Lead and Epidemiology and Surveillance (ABLES) meeting in 2010 to help guide the national program and other states regarding the utility of this endeavor. Other changes to the registry include sending letters advising pregnant women to have their newborns tested at birth; redesigning the interview to computer modules allowing the interviewer to provide appropriate educational information based on responses received; raising the interview level to 25 ng/mL for blood mercury exposures and providing a fact sheet to those reported with lower blood mercury levels; and working more directly with the local health departments on case management.

In addition to those changes, the HMR database was redesigned to an interactive system which is updated daily. Both blood lead and other heavy metal reports are received electronically from laboratories daily, and are added to the database each morning. All surveillance and follow-up information is available to DOH instantly as changes and updates occur. This greatly enhances the ability of DOH to determine if a report has already been received; correct report and case data immediately; make new information directly available to all staff; uncover and correct errors, add new employers, assign cases to interviewers and track the progress of cases with elevated test results, daily. Daily updates allow staff to rapidly respond to highly elevated levels to ensure that the case is receiving proper medical management, to identify others at risk, and to intervene to prevent further exposures.

Appendix C: New York State Network of Occupational Health Clinics

Follow link to the most current list of New York State Network of Occupational Health Clinics.